In 2003, while on an aerial photo shoot near the Golden Gate Bridge, my pilot and I decided to explore the San Francisco Bay Area.

As our helicopter drew near the eastern span that connects Yerba Buena Island and the city of Oakland, I was surprised to see a long series of large, gaping holes in the water. Butted against each hole were barges carrying big industrial cranes and metal pilings.

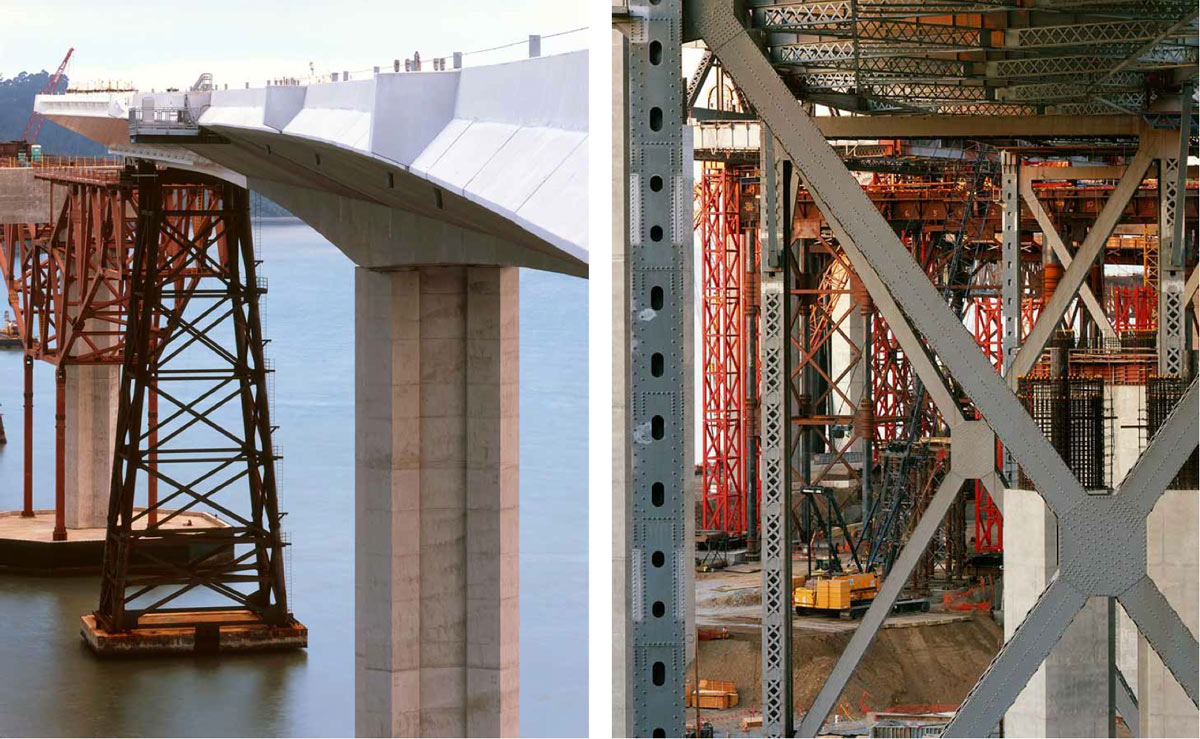

As we slowly flew over one of these odd openings, I was riveted by the sight of a huge, vertical section plunging down through the water. Far down on the base of the section were the tiny figures of men walking around or using heavy equipment. These men were workers preparing the foundations for the new bridge and, to my amazement, they seemed oblivious to the millions of gallons of water held at bay only by the steel walls of the cofferdams. While I had been aware of the Bay Bridge project for years, it was not until that moment that I realized what an immense and important effort it was going to be.

I also knew that I wanted to be a part of this monumental project somehow. Photographing its progression would be my part and, through my art, I could pay tribute to those who designed and built the new bridge across the East Bay.

My passion lies in manmade structures. To me, there is beauty in grand, majestic projects such as power plants and bridges. Each construction is the result of human ingenuity and effort, and through them come the growth and opportunity that fuels our human communities.

Bay Bridge History

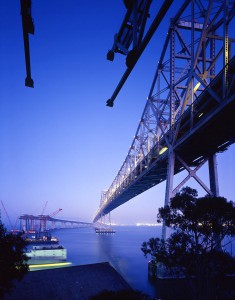

Bridges connect people, and the original San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge faithfully served its connective purpose from the day it opened in 1936. Like the Golden Gate Bridge, which opened six months after it, the crossing enabled people to more easily travel back and forth for work or pleasure, and no doubt contributed to the post-World War II Bay Area boom during the late ‘40s.

The original San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was actually made up of two bridges: a cantilevered eastern span that linked Oakland and Yerba Buena Island, and a suspension bridge that connected the island with the city of San Francisco. Completed first, the rugged, no-nonsense eastern span was used to bring men and materials to the middle of the bay in order to construct the bridge to San Francisco. While the second span was a majestic, four-tower crossing, the eastern span was designed to be purely functional, and it served its noble, plain-faced purpose for 75 years.

Then the Loma Prieta earthquake struck in 1989. Along with the devastation to urban areas, a portion of the eastern span’s upper deck collapsed onto the lower deck. I was standing on a street corner in San Francisco, waiting for the light to change, when the earthquake knocked me to the ground. I also remember the tremendous chaos that ensued. The eastern span had to be closed for repairs for six weeks, paralyzing the entire Bay Area. There was no hiding the fact that the bridge was showing its age and a new span was needed.

Within months of my pivotal flight over the east bay, those gaping holes I saw gave rise to concrete monoliths jutting up and out of the water. These were the footings that would brace the new bridge we see today. Determined more than ever to photograph the bridge construction, I turned to people I knew at the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), one of the organizations in charge of the bridge project.

The Project Begins

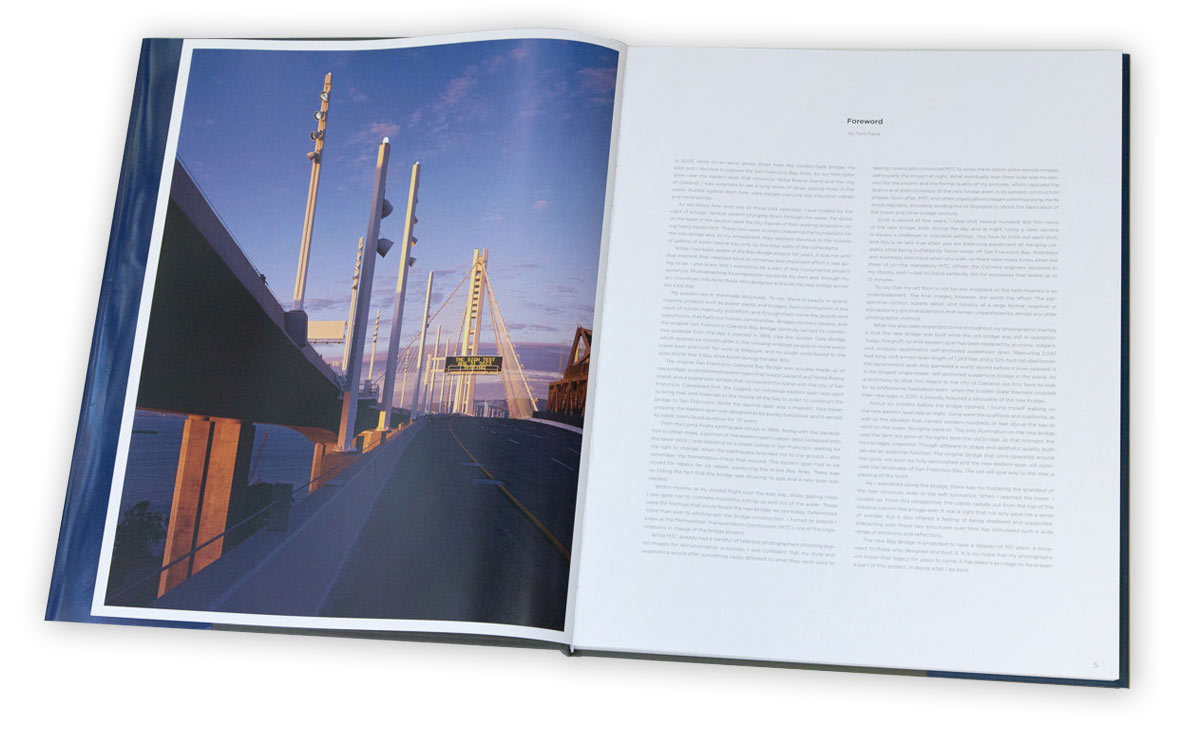

While MTC already had a handful of talented photographers shooting digital images for documentation purposes, I was confident that my style and experience would offer something vastly different to what they were used to seeing. I eventually convinced MTC to allow me to shoot some sample images, particularly the project at night. What eventually won them over was my passion for the project and the formal quality of my pictures, which captured the drama and distinctiveness of the new bridge even in its earliest construction phases. Soon after, MTC and other organizations began commissioning me to shoot regularly, including sending me to Shanghai to shoot the fabrication of the tower and other bridge sections.

I wanted to be a part of this monumental project somehow. Photographing its progression would be my part and, through my art, I could pay tribute to those who designed and built the new bridge across the East Bay.

Over a period of five years, I have shot several hundred 4×5 film views of the new bridge, both during the day and at night. Using a view camera is always a challenge in industrial settings. You have to think out each shot, and this is no less true when you are balancing equipment on hanging catwalks while being buffeted by fierce winds off San Francisco Bay. Walkways and stairways also move when you walk, so there were many times when the three of us – the mandatory MTC officer, the Caltrans engineer assigned to my shoots, and I – had to stand perfectly still for exposures that lasted up to 15 minutes.

To say that my art form is not for the impatient or the faint-hearted is an understatement. The final images, however, are worth the effort. The perspective control, superb detail, and tonality of a large format negative or transparency are characteristics that remain unparalleled by almost any other photographic method.

What has also been important to me throughout my photographic journey is that the new bridge was built while the old bridge was still in operation. Today, the gruff, no-frills eastern span has been replaced by an iconic, elegant, and uniquely asymmetric self-anchored suspension span. Measuring 2,047 feet long, with a main span length of 1,263 feet and a 525-foot-tall steel tower, the replacement span also garnered a world record before it even opened: it is the longest single-tower, self-anchored suspension bridge in the world. As a testimony to what this means to the city of Oakland, we only have to look to its professional basketball team: when the Golden State Warriors unveiled their new logo in 2010, it proudly featured a silhouette of the new bridge.

A New Bridge

About six months before the bridge opened, I found myself walking on the new eastern span late at night. Gone were the scaffolds and platforms, as well as the elevator that carried workers hundreds of feet above the bay to work on the tower. No lights were on. The only illumination on the new bridge was the faint red glow of the lights from the old bridge. At that moment, the two bridges coexisted. Though different in shape and aesthetic quality, both served an essential function. The original bridge that once operated around the clock will soon be fully demolished and the new eastern span will dominate the landscape of San Francisco Bay. The old will give way to the new, a passing of the torch.

About six months before the bridge opened, I found myself walking on the new eastern span late at night. Gone were the scaffolds and platforms, as well as the elevator that carried workers hundreds of feet above the bay to work on the tower. No lights were on. The only illumination on the new bridge was the faint red glow of the lights from the old bridge. At that moment, the two bridges coexisted. Though different in shape and aesthetic quality, both served an essential function. The original bridge that once operated around the clock will soon be fully demolished and the new eastern span will dominate the landscape of San Francisco Bay. The old will give way to the new, a passing of the torch.

As I wandered along the bridge, there was no mistaking the grandeur of the new structure, even in the soft luminance. When I reached the tower, I looked up. From this perspective, the cables radiate out from the top of the massive column like a huge web. It was a sight that not only gave me a sense of wonder, but it also offered a feeling of being sheltered and supported. Interacting with these two structures over time has stimulated such a wide range of emotions and reflections.

The new Bay Bridge is projected to have a lifespan of 150 years, a testament to those who designed and built it. It is my hope that my photography will honor that legacy for years to come. It has been a privilege to have been a part of this project, in doing what I do best.

<<<—>>>

Special thanks to the Bay Bridge designers, T.Y. Lin International/Moffatt & Nichol, Joint Venture, for their generous support of this book.